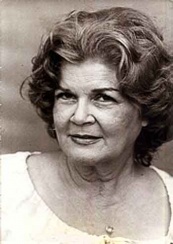

4.1.3.3.2 The poetic work of Carilda Oliver Labra (1922 – ) in the 1950s

During the 1950s, in addition to “Memory of Fever” (1958)—a text that will be discussed in another section—Carilda Oliver Labra published other lesser-known collections of poetry within the context of her work, such as “Lyrical Biography of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz” (1951), which earned her the National Prize awarded that same year; and “Notebook of the Newlywed” (1952), whose title establishes a certain intertextual dialogue with “Diary of a Newlywed Poet” (1953) by Juan Ramón Jiménez.

The first of the works mentioned has apparently not been published in Cuba, at least not before 2002, it consists of a series of 10 poems in which the poet from Matanzas addresses specific moments in the life of the Mexican, birth, beginning of writing, love, loss of love, death and others, are recreated with an empathetic devotion that is woven from the similar condition of rebellious women (although Sor Juana’s rebellion was rather in the confines of the intellect and the spirit) and crosses the secular distance.

The following verses belong to the poem entitled “He falls in love”:

“Juana de Asbaje is saved

the heart where dreams

(Love suddenly calls her,

violent against silk).

Touch a color you like,

walk towards spring

and hear the blood beating

like spilling party

there in his recent body

of a girl who plays at being a boyfriend…

For its part, “Notebook of the Newlywed” consists of 20 poems in which the author refers to the March of her honeymoon, thus dating, specifying the time, the gradual growth of love. This is a poetry that takes shape from its circumstances, moving as the lovers pass through the supposed sands of Varadero, through the city streets, with the metamorphosis of the girl into a woman who saves her dreams.

The text was prologued by the poet and at the same time a good friend of the Matanzas native, Agustín Acosta, with whom the poet shares certain affinities; although Carilda leans toward a neo-romanticism that already has certain colloquial nuncios here, currents she knew how to fuse like no other poet of her generation.

In these verses the author opts for closed forms, in a graceful versification in which she already uses the resources of lexical surprise and other elements of the poetic avant-garde, without becoming avant-garde, since she never abandons herself to the exclusive realm of words and linguistic experimentation, but rather maintains an anchor in reality, but immediate for the senses and not precisely intellectualized.

Regarding this collection of poems, Agustín Acosta says: “Carilda Oliver is unlike any other poet. The everyday spiritual is an almost constant motif in her poetry. It doesn’t matter if the impression of a common event lacks spirituality: she communicates her own, and the event appears spiritualized.”

Spirituality is here above all the space in which love has its seat, since the Carilda of high-flying erotic poems has not yet emerged, we can already appreciate that area of her poetry that can be called homely, highlighting the small things that make up existence, sometimes poetry that is made with spices and kitchen ingredients, but that transmits a sensitivity that distinguished her already in those years as a singular promise of Cuban literature.