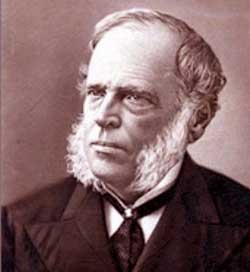

2.2.7 The historiographical and scientific work of Antonio Bachiller y Morales (1812 – 1889)

The conceptions of Antonio Bachiller y Morales are in many ways heirs to those of José Antonio Saco; a spokesperson for the ideology of the Creole slave-owning bourgeoisie, he excluded Cuban blackness and its African origins from the process of national formation, although he also studied them. One of his last works was precisely “Los negros” (The Blacks), published in 1887, shortly after the official abolition of slavery was decreed. In it, he records the history of this institution and also traces the course of abolitionist ideas in Cuba.

Politically, he joined the reformist movement and even maintained an autonomist stance even after the end of the Ten Years’ War. This doesn’t necessarily mean he didn’t love independence; but his pacifist and hardly revolutionary attitude was above all else. He believed in an evolutionism without ups and downs and without radical metamorphoses, which would lead per se to independence, without bloodshed. He saw science as the exclusive vehicle for this evolution.

In this sense, he delved into the study of various sciences and contributed to the founding principles of others that would emerge later. Mariana Serra points out the following: linguistics, archaeology, anthropology, ethnography and other more consolidated disciplines, such as ethics, aesthetics, law, political economy and history, with erudite but not always profound and less documented results than it may seem at first reading.

One of his most valuable works in the field of historiography, according to many of his exegetes, was undoubtedly “Notes for the History of Letters and Public Instruction on the Island of Cuba” where he republishes articles published in various magazines and newspapers and includes new data. His vision of history is rather idealistic, giving a primordial role to figures rather than to the deterministic concatenation of events.

Bachiller y Morales is also considered the father of Cuban bibliography, for his catalog of periodical publications and books and pamphlets that were published between 1781 and 1840. As an educator, he managed to transmit to his students part of the great cognitive arsenal he possessed, one of his disciples, José Ignacio Rodríguez, would express in this regard: “None of us knew that there was communism and a German philosophy, and rationalist schools and practical philosophy, until we entered the Bachiller class, which put us in contact with all the people of modern times.”

For his part, José Martí would not fail to praise Bachiller’s virtues: “that astonishing industriousness, key and auxiliary to all his other virtues, (…) those shelves of knowledge that made his capable mind, like an Alexandrian library, (…) that moral candor that in dire times, and with his master’s boot on his forehead, kept him entertained, as if doing housework, in investigating the most hidden curiosities of his Cuba, of his America, and the most varied ways of being useful to them…”

Even though his work was more scholarly than innovative, and his political ideas did not contribute to opening the intellectual path to independence, the truth is that he was always driven by the desire to serve his fellow citizens and bring to the present, to the island’s reality, a reflection of the past and the knowledge of his time.