2.4 Development of the costumbrista article in the period 1790 – 1868

The following definition appears in the dictionary of Cuban literature: “The term costumbrismo designates that form of realistic literature, characteristic of the rising bourgeoisie, which is concerned with portraying and describing the representative types of that same class and society. In all stages and genres of literature, there have been occasional descriptions of customs, modes of collective existence, and characters representative of the various social classes. (…) But costumbrismo, as a genre, as a peculiar form of literary expression with its own characteristics, did not appear until the rise of the bourgeoisie.”

The description of certain customs has been at the very heart of national literature; however, it only acquires substance in the progressive differentiation of Creoles and the formation of the bourgeois social class. More than a genre, it is a breath that permeates almost all genres, especially embedded in narrative and specifically in the novel.

Renowned storytellers and poets cultivated the article on customs as an independent genre, such as Manuel de Zequeira himself, whose texts usually appeared in the Papel Periódico. Descriptions of customs also intertwine in his poetic production. They are present, although not as a defined purpose, since Silvestre de Balboa’s work, “Mirror of Patience,” so the long presence of germs of customs in our literary production can be appreciated.

Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros’s “Daily Scenes,” published in 1840, also constitute an important moment in the genre of costumbrismo (costumbism), as do José María de Cárdenas y Rodríguez’s articles from 1847, which deserve separate consideration. Anselmo Suárez y Romero explored this theme both in his novel “Francisco” and in texts of this nature published in the press. In the field of novels, independently studied texts stand out, such as the first “Cecilia Valdés” by Cirilo Villaverde, and, in general, almost all the published titles touched on or were definitely inscribed within the genre of costumbrismo.

Antonio Bachiller y Morales also published articles on customs; but from a more scientific perspective that sought not only to show mere types but also to unravel the background and realities that gave rise to them. This approach would have followers throughout the remainder of the colonial period and even beyond.

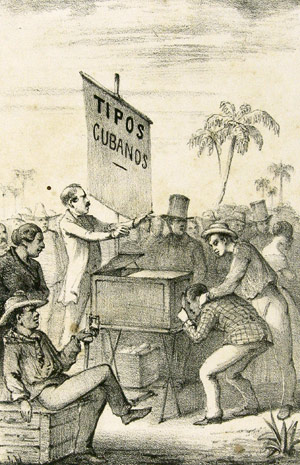

The anthologies of articles display a clear intention toward differentiation, achieved precisely through a national voice that emphasizes the uniqueness of Cuban culture through language. The first of these, which echoes the title of others that appeared in Europe, was “Los cubanos pintados por sí ellos” (Cubans Painted by Themselves), published in 1852. It received some unfavorable reviews, such as that of Idelfonso Estrada y Zenea; however, this does not diminish its value as a seminal collection whose very existence contributed to enhancing costumbrismo as a social and artistic form of writing.

It is curious that this compilation was edited by a Spaniard, Blas San Millan, who states in his introduction: “Nations are like individuals; the slightest foreign sarcasm sharply wounds our nationality, and we do not forgive those who were not born on our soil, whether truthfully or untruthfully, who sneer at us, or even advise us (…) Cubans have also sought to paint a picture of themselves and (…) both in good and bad ways, show their worth: their attempt is not to create caricatures, but rather portraits of given and exact types, not individualities, but general phenomena of the population and its customs in each class…”

This collection would continue into the war period, when the independence struggles had already, to a certain extent, inflamed the collective spirit and Cubans were in the process of transformation as part of the national identity.