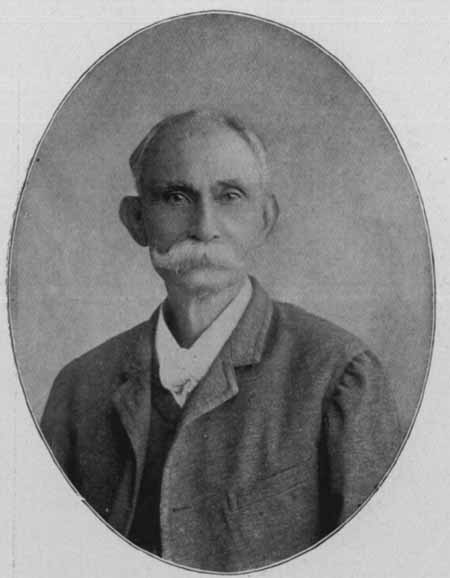

3.5.8 Testimonial pieces written after the end of the Ten Years’ War, the documentary legacy of Máximo Gómez (1836-1905)

Although distant in time, there were several interpretations of the meaning of the feat and within it the passage of the capitulation at Zanjón, an iterative point in war literature, perhaps because the protagonists needed to conjure it through expression, to analyze it until it was exhausted in order to begin a new conspiratorial task, one that would inherit the best war tradition of the decade 1868 – 1878.

Shortly after the events, two works bearing the same title, “Convenio del Zanjón,” by Máximo Gómez and Ramón Roa, were published from two Cuban emigration centers, Kingston and New York. Both are defenses of the authors’ stance; but above all, they directly address the causes that led to such an outcome, centered on disunity on all battle fronts.

Máximo Gómez also published other narrative texts that illustrate little-known battles and combatants of the Ten Years’ War, with the same direct style that characterized his tenure as a military leader.

Among these texts are “El viejo Eduá” and “El héroe de Palo Seco,” published in Cayo Hueso in 1892 and 1894, respectively. He also wrote “Mi escort” and “La odisea del general José Maceo,” which follow the same line of vindication of unknown passages and anonymous protagonists. In his personal diary, he recorded not only the events of the Ten Years’ War but also all his conspiratorial work from 1868 to 1898.

Gómez handled the springs of the epic with considerable ease, which is evident in the narrative connection of “The Hero of Palo Seco,” a term he uses to refer to Lieutenant Colonel Baldomero Rodríguez, whose actions he places at the forefront of the battle: “Lieutenant Colonel Baldomero Rodríguez survived his act of heroism at Palo Seco, always adding brilliant notes to his service record (…) Sleep in peace, bold and daring warrior; your memory has not died nor can it die for your comrades who fought alongside you for the redemption of the Homeland.”

In “El viejo Eduá,” he refers to a 60-year-old slave who served him unconditionally as an assistant; this story stands out for its focus on the life of a representative of the most neglected segment of society. It also reveals a surprising understanding of human feelings through the character of Eduá.

Gómez, as a man of action, managed to capture the action with considerable fluency; although he did not fully master the tools of the language, he instead used humor and other resources that give his texts an interest beyond that of mere testimony. His work is associated with the romantic-nationalist historiographical movement, as some scholars have termed it, and presents a notable interest in understanding the nation’s warlike future and how this would crystallize in literature.