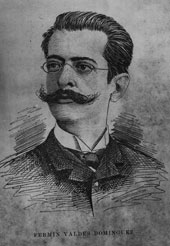

3.5.10 The “Soldier’s Diary” by Fermín Valdés Domínguez (1852 – 1910) and his journalistic work

Fermín Valdés Domínguez was not known for a highly refined literary style, but rather for his meticulous observation and portrayal of the events in which he was immersed. He has gone down in history primarily for being a classmate and friend of José Martí, and for both having been jointly accused of activities that the colonial authorities considered conspiratorial.

He was also among the medical students accused of desecrating the tomb of the Spaniard Gonzalo Castañón, and eight of his classmates were executed. This is why he wrote the testimonial cited in another section: “November 27, 1871.” By that time, he had already made his first forays into journalism, with texts that appeared in “El diablo cojuelo.”

Although a doctor by profession, he was interested in literature and sponsored gatherings attended by José Martí and other literary figures and intellectuals of the time. He also published several texts in El Cubano, El Triunfo, and El País. He supported the apostle in the development of the independence movement, even representing the Cuban Revolutionary Party in Venezuela and later in New York, and contributed his intellectual contributions to the newspaper Patria.

In 1895, he joined an expedition under Carlos Roloff, rose to the rank of Colonel, and held, among other positions, the position of Chief of Staff to General Máximo Gómez. For all these reasons, his campaign diary has a high testimonial value, both for the official documents it reproduces and for his recollections of his contacts with Gómez and his recollections of Martí.

The text also includes a section dedicated to the emigrants from Florida, important for understanding the extent to which their work had contributed to the development of the Gesta, especially in Key West: “The Cubans went to the Keys in search of free land to work, and there they brought their love for their homeland tyrannized by Spain. And all those workers joined together in defense of the home they had been forced to abandon. Their sociability and mutual affection made them studious and cultured, and for their meetings they founded a temple in “San Carlos,” where they consecrated their faith in the vindication of their homeland, and they sought in school and on the platform the invigorated strength of spirit they deemed necessary to one day demonstrate that they were worthy of being considered free citizens, capable of maintaining in their own Republic the correctness and purity that gives people an honorable place.”

Patriotic ideals are present throughout Valdés Domínguez’s body of work. The length of the clauses somewhat hinders reading, and the style is uneven; however, his work contains passages of some aesthetic achievement and particular historical value. After the conclusion of the insurrectionary struggle, he continued his activity in medicine and the natural sciences in a broader sense; from a historical and literary perspective, he published texts in Patria y Libertad, La Reforma, and El Fígaro.

José Martí would say about this, one of his dearest friends: “Sacred is he who, in the robustness of life, with love at the head of the comfortable table, threw the table back, and the advice of cowardly love, and served his people, without fear of suffering or dying: and that is Valdés Domínguez.”