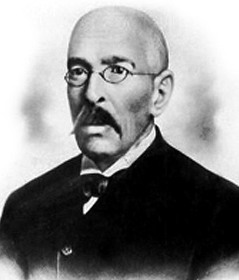

3.7.3 Rafael María Merchán (1844 – 1905), his foray into literary criticism

Rafael María Merchán was also one of the Cuban literary critics who strongly adhered to the independence movement; he sometimes used this political stance as an aesthetic filter, so his writing doesn’t always convey objectivity. In his youth, he worked as a typographer and typesetter, and these were his first contacts with the world of the written word.

In addition to his political actions, some of which have been addressed in the section on oratory, he left behind interesting critical reflections, the ideological core of which can be found in his two main texts: “Critical Studies”, published in 1876 and “Variedades”, in 1894, both in Colombia, a country where he had apparently settled since 1874 or between the following two years and where he carried out part of his political work and literary criticism.

Some of his opinions were expressed in the context of a bitter polemic he had with the Spanish critics Juan Valera and Vicente Barrantes, the reason for the latter being an article published by him in the newspaper “España moderna”, apologetic regarding the book “Lyric Poetry in Cuba”, by Martín González del Valle, a Cuban living in Spain, which denigrated Cuban lyric poetry and implicitly its nationality.

In short, Merchán responds with an ironic article entitled “El espinar cubano y la segur barrantina” (The Cuban thorn bush and the Barrantina segur), in which he rightly points to the extra-literary factors that had led to a certain delay in the evolution of Cuban poetry, essentially the Spanish colonial siege, which also imposed on the development of ideas and also weighed on collective subjectivity.

In the context of this controversy, he published another article of the same nature, entitled “De todo” (On Everything), in which he dedicated himself to highlighting the historical and literary stature of José de la Luz y Caballero, about whom many texts were written that sought to obscure his true revolutionary character.

Other texts by the author that reveal interesting insights are worth mentioning: “Poems of Juan Clemente Zenea,” “Stalagmites of Language,” “Bécquer and Heine,” and “The Seven Treatises of Montalvo.” Many of his aesthetic tendencies, in which formalism and a sometimes exacerbated analytical predisposition prevailed, can be traced in the cited texts and in the introductory notes to some of the books he wrote forewords.