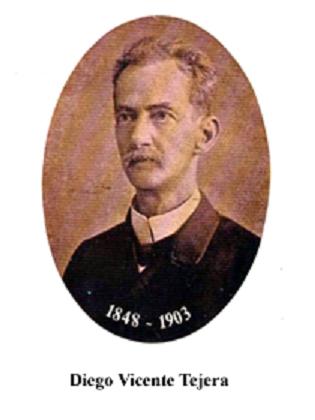

3.7.5 The work of Diego Vicente Tejera (1848 – 1903) in literary criticism

During his youth, Diego Vicente Tejera lived in several countries in the Americas and Europe: Puerto Rico, the United States, France, England, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Venezuela, Mexico, and others. This allowed him to accumulate a wealth of political and cultural experiences and information that would contribute to his work as a literary critic. Although he did not dedicate himself to this role, he left behind balanced and insightful judgments.

In his 1895 text “A Little Prose,” he attempts to define the boundaries between the romantic novel and the naturalist novel—which he also calls the realist—and offers interesting disquisitions that, although imprecise, contributed to clarifying the meaning of both currents; above all, the role that positivism and, in general, scientific discoveries were destined to play in the naturalist novel, although creative imagination was not absent from it.

Tejera also referred to Cecilia Valdés, but adequately weighed her values and those of Cuban narrative as a whole, exaggerating somewhat since he intended to respond to a seemingly non-malicious judgment by Benito Pérez Galdós, who, after reading Cirilo Villaverde’s work, had inspired the comment that he did not think anything so good could be written in Cuba.

A bias that somewhat obscures Tejera’s work, evident in this and other texts, is the undervaluation of Spanish literature. He attacks Antonio Hernández Grillo and other contemporaries; it seems the author’s own separatist ideological background unconsciously influenced his literary judgments.

In his article “Les Dames de Croix-Death,” he introduced some concepts that shed light on the relationship between literature and reality, handled differently by prevailing aesthetic beliefs, without considering any coexisting tendency superior to the other but rather as modes of literary realization. His style is not always identifiable, but it is characterized by clarity, conciseness, and a fairly measured attitude when issuing assessments in this complex field.

His political writing—both pro-independence and promoting socialism—and his literary and critical texts were published in various contemporary media, both in Cuba and abroad. These include: “La Abeja Recreativa” and “El Ramillete” in Spain; “La Verdad” (The Truth), the organ of the Revolutionary Junta in New York; “El Ferrocarril” and “Revista Veracruzana” in Mexico; and “El Triunfo” (The Triumph of Havana Elegante), “El Porvenir” (The Triumph of Cuba), “El Tábano” (The Tender), and “El Fígaro” (The Figaro).