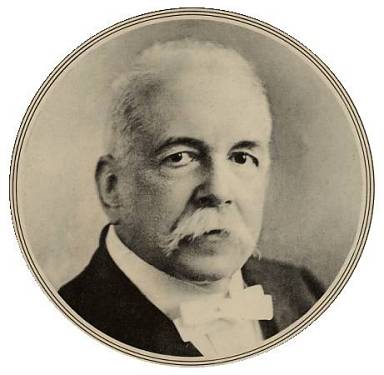

3.7.6 Literary criticism by Enrique José Varona (1849 – 1933)

Enrique José Varona left behind interesting reflections not only for literary studies but also on art in a broader sense, such as those contained in his 1883 study, “Social Importance of Art,” in which he points out its social purpose and its mission to reflect collective feelings and experiences, implicit in the so-called universality to which it should strive according to more contemporary precepts.

Varona also participated in the rise of positivism as an epistemology in Latin America, applied to literary studies. He emphasized the relationship between the island’s literature and the American scene, as reflected in his 1876 text “A Glance at the Intellectual Movement of America.” From his youth, he immersed himself in the world of classical literature and the mother tongues; but this did not prevent him from understanding that the value of works should be appreciated in relation to the era in which they were conceived, and not in an absolute sense.

His literary vision encompasses both the universal and the indigenous. The former is evident in his 1883 lecture “Cervantes,” in which he delves into the writer’s personality and the linguistic magic at work in his work. In “The New Edition of Plácido,” from 1886, he undoes and harshly criticizes the corrections of previous editors, allowing the lyrical personality of the mulatto poet to flow. He also advocates for the creative freedom of the author in the face of state or religious institutions.

In 1883, he also published the book “Literary and Philosophical Studies,” a landmark in its Latin American context. His most mature literary meditations appear in “Six Lectures,” from 1887, and “Articles and Speeches: Literature, Politics, Sociology,” from 1891, while continuing to incorporate critical political questions about the Spanish colonial system.

His activity after the revolutionary outbreak of 1895 was more political than literary. He took over the editorship of the newspaper Patria after José Martí’s death in Dos Ríos, responsible for revolutionary propaganda; however, he still published some critical texts.

Although his work in public and academic positions took up a lot of his time, he did not abandon his literary criticism, sometimes in the introductory notes to his works, as in the case of “Sombras eternas” (Eternal Shadows), 1919, by Raimundo Cabrera, and “Poesías” (Poems), by Luisa Pérez de Zambrana.