3.8.1 The poetic work of José Martí (1853-1895)

On January 28, 1853, Paula Street, in the Havana suburbs, witnessed the birth of one of Cuba’s most illustrious sons: José Julian Martí Pérez. He was a disciple of Rafael María de Mendive and José de la Luz y Caballero, who instilled in him the revolutionary ideas that defined his future vocation: to fight for the independence of his beloved homeland.

He was still a teenager, just sixteen years old, when he was sentenced to six years in prison for writing a letter to a friend who had decided to join the volunteer corps in Havana, accusing him of being stateless. Thanks to the efforts of his mother, Doña Leonor Pérez, due to his delicate health from years of forced labor in the San Lázaro quarry, he was deported to Spain in 1871. In 1874, he graduated in Law and Philosophy and Letters from the University of Zaragoza.

Recognized worldwide as the founder of Latin American Modernism, he explored various literary genres such as poetry, novels, theater, and journalism. Although his artistic creation sometimes falls short of all the defining characteristics of this movement, his formal contributions to it cannot be denied.

Martí opposes the elaborate language of Parnassianism, as well as the mournful tone of the Romantics. His poetry is written with complete naturalness and simplicity, without rhetoric, with words that spring from his soul. He expresses this in his Simple Verses, specifically in poem V:

“My verse pleases the brave:

My verse, brief and sincere,

It is of the vigor of steel

With which the sword is cast.”

An important factor in Martí’s work is the people, the American people, long dispossessed and enslaved: inspirational. For them and for them, Martí writes with simple and beautiful words, ensuring that his message resonates powerfully with the most humble:

“Hidden in my brave chest

The pain that hurts me:

The son of an enslaved people

Live for him, be silent, and die.”

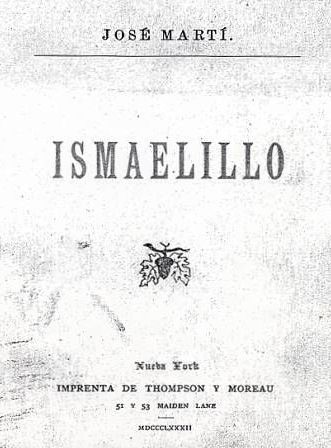

For José Martí, the feeling of grief was inseparable from literary creation. This feeling accompanied him for much of his life: he lived with the pain of not being with his son, to whom he dedicated the poetry collection “Ismaelillo,” and above all, he suffered from seeing his beloved island languishing as a Spanish colony. This stanza from poem XLVI of Versos Sencillos illustrates this:

“Pour out, heart, your sorrow

Where it cannot be seen,

For pride, and for not being

Cause of pity.

I love you, my friend,

Because when I feel the chest

Already very loaded and undone,

I share the load with you.

You suffer me, you lodge

In your loving lap,

All my painful ardor,

All my desires and affronts.”