3.8.4 The art of oratory in José Martí (1853 – 1895): Its beginnings

In Cuba, sacred oratory experienced significant development in the 18th century. During this period, as the island was a Spanish colony, it was impossible to hold public political debate, so the sacred pulpit became the only platform permitted for the development of this laudable genre.

In the 19th century, the historical and social context changed as a result of the independence struggles on the American continent. Therefore, political discourse became an effective tool for gaining sympathies for the revolutionary cause. The more eloquent the speaker, the more the ideas resonated with the listeners, generally illiterate or semi-literate people, who could only understand what was happening through oral communication.

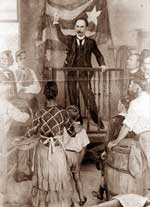

José Martí, a highly talented scholar with a broad culture and command of the language, who dedicated himself since the end of the 1880s to organizing the so-called Necessary War, made this genre a powerful weapon for the cause: “Trenches of ideas are worth more than trenches of stones,” said the man who was a sublime orator.

Manuel de la Cruz characterized him this way: “His vehemence was the soul of his oratory. It is therefore easy to understand how he could have been a popular orator, extremely popular, to the point of arousing idolatry, being by nature an orator of an elevated, essential, and profoundly literary style, quintessential and often obscure. His vehemence vibrated even in the timbre of his voice; according to those who heard him regularly, few orators have given their words the tone, warmth, and force that Martí imparted to his speeches. He was an improviser, and his memory was never unfaithful to him, even when he climbed the podium with no more preparation than the overwhelming fatigue of daily work, all of it purely mental labor […] This explains and understands how he successfully completed the work to which he devoted all his efforts, turning the affiliate into a sectarian, a political fanatic, a believer in whom the power of faith determined effective action, who neither hesitated before sacrifice nor flinched before the holocaust.”

His beginnings in oratory were very early, when, on March 4, 1870, before a Spanish court that was trying to clarify who had been the main author of the letter condemning Carlos de Castro, whether José Martí or Fermín Valdés Domínguez, Martí assumed full responsibility for the event, this being his first victory as an orator.

At 24 years of age, as a literature professor at the Guatemalan Teachers’ College, he captivated the audience gathered that day to participate in the meetings organized by the school’s director, which allowed students to interact with various figures from the country’s intellectual life, by speaking about a book by the Guatemalan poet Francisco Lainfiesta.

From that moment on, due to the vigor of his words, the tone and nuances he imparted to his voice, the exquisiteness of his vocabulary, and the empathy he managed to establish with his audience, his words began to be requested on numerous occasions, and he became a master of this art.

His words captivated all audiences: aristocrats, diplomats, Cuban upper middle class, cigar makers, and peasants. As his fame as a writer, poet, and journalist grew, so did his as an orator. In his speeches, he never ceased to reflect, whether through subtlety or directly, his feelings and thoughts regarding the need for Cuba’s independence from Spain.