5.2 Distinctive features of Cuban popular music in the 17th century.

In 17th-century Cuba, the people had in their hands instruments and rhythms that left their mark on dance and song. Diverse elements fused, giving rise to novel metric combinations in melodic and poetic treatment. The repetitive nature of the imported patterns did not prevent the predominance of movement and change.

It is noteworthy that at the beginning of the century, around 1605, he offered to teach organ and singing classes, probably being the first music teacher that the Cuban population had ever known: Gonzalo de Silva.

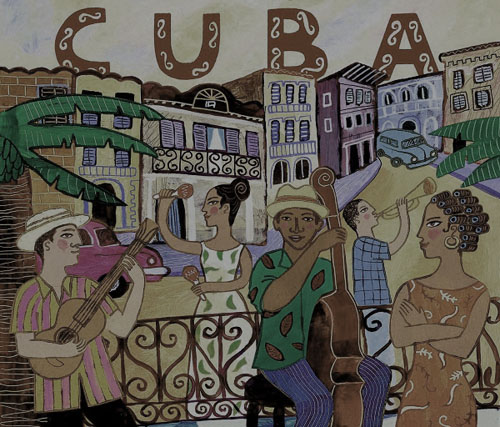

On the island, blacks and whites shared a certain preference for specific rhythms and melodic turns that were becoming typical, so popular music began to significantly outstrip official music. From the beginning, something spontaneous happened: the people, in their moments of expansion, drew on what was closest at hand. Whites and blacks made their music, freely blending Spanish and African elements.

In Havana, this mixture was reflected in the songs and dance styles of the people. Relations between the ports of Havana and Veracruz facilitated the exchange of melodies and rhythms. These were not always well received by the clergy.

Love songs, sentimental songs, and picaresque songs, each with a Spanish flavor and rhythm, more or less modified by the influence of the tropical environment, constitute the musical heritage of Cuba since the mid-17th century.

In our archipelago, during the 17th century, processions abounded, with a distinctive, half-Christian, half-pagan aspect. The images alternated with carnival dolls. There were street shows and popular entertainment, always celebrated with music.

During this period, life with music became more bearable in the convents. It was one of the most deeply rooted traditions in Spain. It was imported to the colonies, becoming immortalized in Cuba. Well into this century, around December 25th, one could occasionally see a jota or fandango being danced in a convent. To the clatter of tambourines and castanets, the confinement was forgotten, and regional songs that had arrived in Cuba long before by various means were then repeated. These songs reached the island and were later creolized, acquiring their own characteristics, in which the intermixture of races was evident.

We owe the Cuban people’s happy disposition toward verse to the octosyllabic verse, our finest Iberian heritage. It had also been imported by the conquistadors in fragments of ballads. It was presented in Cuba in various forms, with the stanzas becoming shorter. Those with shorter stanzas often corresponded to rustic or peasant songs, as was the case initially with the villancico, which must have been heard more than once in Cuba at the beginning of the 17th century.