9.2.3 The Sucu-sucu.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the expansion of the sugar industry brought with it the migration of Jamaicans and Puerto Ricans, who settled mainly in Camagüey and the eastern part of Cuba. Between 1915 and 1935, new musical forms evolved in Cuba, including Sucu-sucu, a form of son first known on the Isle of Pines.

On the Isle of Pines, the cultivation and exploitation of grape groves and timber forests was encouraged, employing a diverse workforce, including Jamaicans and other immigrants from the Cayman Islands, who also brought their cultural elements. Sucu-sucu, changüí, plena, and other Caribbean rhythms from this period bear close ties to one another in terms of musical rhythmic patterns and “escobillado” dance styles.

Little has been said about this dance rhythm. Scholars attribute the origin of this genre to French Guiana, while Cuban researchers defend its origins in the Canary Islands. The truth is that it was very popular, especially in the political and social environment of the early 20th century in that region of Cuba.

This Cuban musical genre features the predominant use of the güiro and a machete scraped with a metal rod. The tres, marimbola, maracas, bongos, claves, and a metal scraper are also present in this genre. It features a very lively, couple-oriented dance with skipping steps, which is still popular in certain parts of the country.

The performing group includes a soloist and a choir that always sings a single tune. The soloist’s sense of improvisation, based on a quatrain or tenth, is very important. The choir is a very important rhythmic element in Sucu-sucu, as it alternates with the singer several times in a single piece.

Among the best-known Sucu-Sucu songs are “Domingo Pantoja” and “Felipe Blanco,” attributed to Eliseo Grenet. The latter referred to Felipe Blanco, who governed the Isle of Pines during the Spanish colonial period, who denounced those who didn’t work. From this came the Cubanism, which refers to when someone isn’t working, saying: “he’s throwing a majá,” “he’s majaseando” (he’s majasing); part of the lyrics say: “The majáes don’t have caves. Felipe Blanco covered them up, covered them up, covered them up, Felipe Blanco covered them up.”

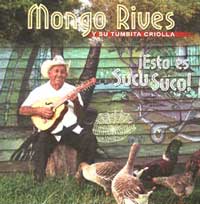

Better known abroad than in Cuba, Sucu-sucu currently has its greatest exponent in the musician and composer Ramón Mongo Rives, a farmer from the Isle of Youth who leads the group La Tumbita criolla. Mongo’s home has a school where he teaches the little ones the secrets of this authentic genre.

The Sucu-sucu rhythm is contagious and very Cuban; the dancers don’t move their shoulders or hips, which identifies it, in this respect, with the oriental son.

And while Cuban society is shaken by the rhythms of recent times on the Isle of Youth, Sucu-Sucu maintains its love for its native rhythm, which has Mongo Rives as the embodiment of a true legend.