3.5.7 “January 6, 1872”, testimony of Melchor Loret de Mola y Mora

The episode that occurred on January 6, 1872, in the Camagüey savannah of Magarabomba, although not isolated in the context of the war and the bitter cruelty of the Spanish troops, does contain gruesome features worthy of fiction literature, and whose testimonial expression is not frequent given that human suffering does not always find words for itself.

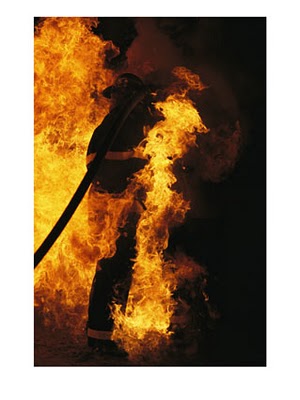

The author was only 8 years old when the events took place and was the only survivor of the massacre committed against his family by two soldiers from the colonial troops, who broke into a hut at midnight and attacked the women and children living there with machetes, members of the Loret de Mola family, and then set fire to the remains, including the body of the author’s two-year-old sister.

The text is divided into seven chapters, throughout which dramatic tension builds, assumptions regarding the presence of Spanish troops in the vicinity of the area that are confirmed, and the fear that is like a latent predetermination of what will happen, all in a faithful copy of the rural reality and the defenselessness of the women and children who lived in the territories disputed in the insurrection.

Melchor Loret had no training as a writer, but he did possess a natural talent for description, combined with a wealth of experiences and emotions that were triggered as he delved into the most harrowing passage of his personal history.

The author continues the narrative even after the massacre, his own awakening of consciousness in a landscape of death and desolation, the infant’s confrontation with death, not as an individual, but rather with all living things that had constituted his space until that moment. The flight, the wandering, and the loneliness he endured for two days until he came across a family who welcomed him constitute the dramatic culmination of the text, whose truthfulness, more than verisimilitude, is what impacts the reader.

A first reading suggests the denunciation of a crime committed during the War; but in its background, one also sees the finger of blame pointed at Spanish colonialism. As with the text “El Ranchador”—a story with a more diluted, real-life reference—the work unwittingly reveals that any type of subjugation deforms the human nature of both its protagonists and its victims, thus having profound accusatory implications that support the need to continue the struggle for national independence.